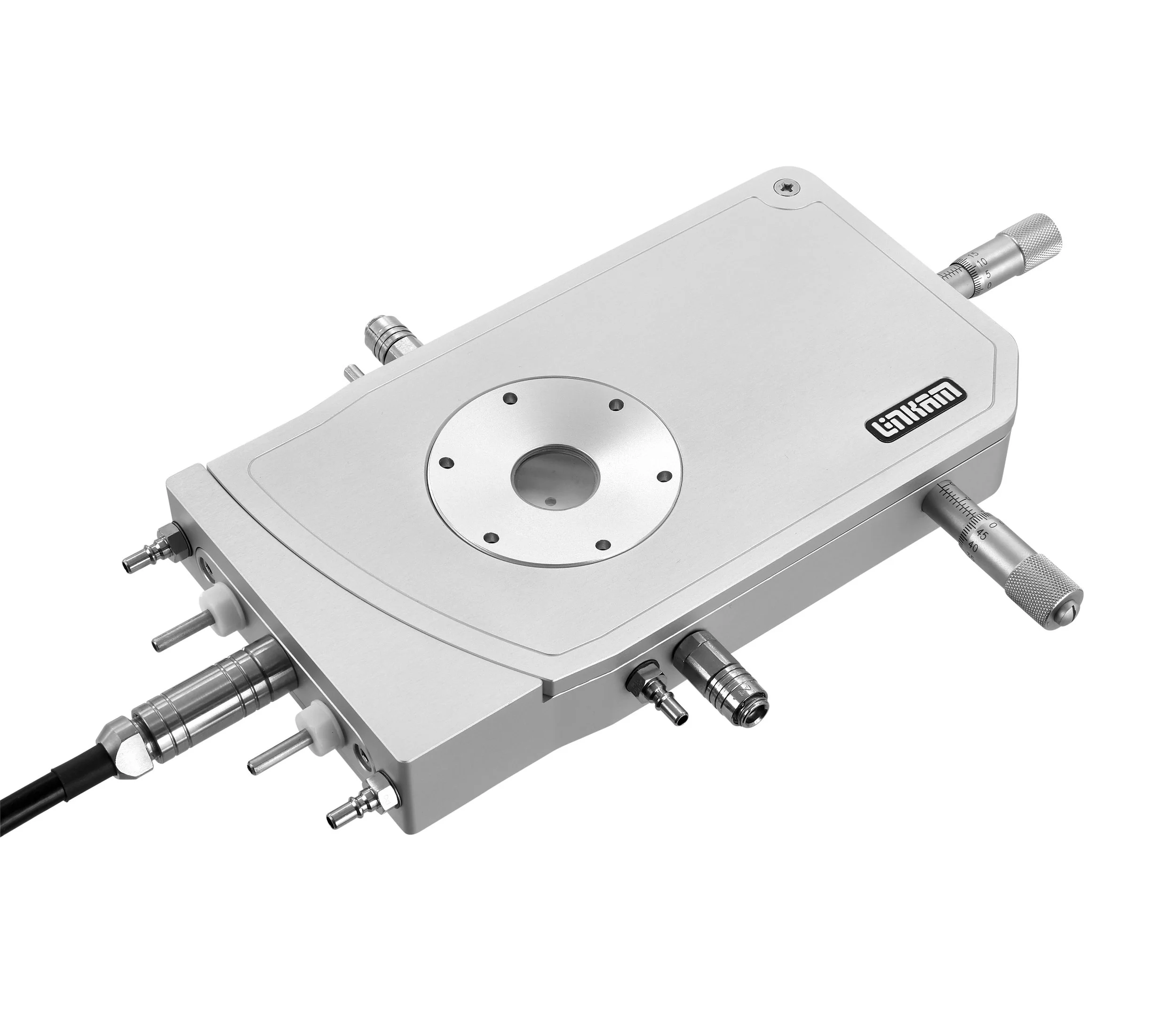

LTS420 shown above

Electronic skins (E-skins) that can mimic the functions of a human skin have been intensively studied in the past few years. They are expected to have a great impact on the upcoming generation of portable and wearable electronics related to the Internet of Things. Even after many breakthroughs in the material sciences, there are still difficulties in achieving high performance and highly functional sensors durable enough for continuous monitoring of human activity and health.

Advanced micro- and nanoscale materials within polymer-based protective layers have been successfully applied for the E-skins. However, it is not only important to study and understand the behavior and properties of these electronic materials, but also to create smart structures to achieve the desired performance for these devices.

A research group from University of Oulu in Finland bypassed common performance and functional issues by combining advanced materials and an ingenious structure to achieve mechanosensitivity to different stimuli, high sensing performance, and functionality within the device. The structure not only provided simultaneous ability to be adhered to a human skin or be attached to clothes or textiles, but also possibilities for precise tuning of the response to achieve optimal performances for different locations in the human body. The devices were able to record human activity and health in a reliable manner, providing adequate long-term durability with machine washability.

The group used a TST350, now superceeded by the LTS420 to test the tensile properties of their sample. When asked about the purpose of the stage, author Jarrko Tolvanen explained: “In our research the Linkam TST350 stage has provided a reliable way to record the stress-strain curve of various materials. Also, this stage has enabled easy and quick way of testing the mechanical properties under controllable temperature and humidity conditions, that could be proven advantageous when further improving and optimizing the performance of a strain sensor.”

Although more testing is required for long-term durability and environmental stability, the group’s work is a promising start in achieving high performance wearable sensors.

Read the research here